Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals

58 Canal Circular Road,

Kolkata - 700054, WB, India.

Contact : +91 9874167730 / +91 9830363642

Email : pchakrabarti@usa.net

Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals

58 Canal Circular Road,

Kolkata - 700054, WB, India.

Contact : +91 9874167730 / +91 9830363642

Email : pchakrabarti@usa.net

INTRODUCTION:

A percutaneous renal biopsy may be obtained for a number of reasons, including establishment of the exact diagnosis, as an aid to determine the nature of recommended therapy or to help decide when treatment is futile, and to ascertain the degree of active (ie, potentially reversible) and chronic (ie, irreversible) changes. The degree of active or chronic changes helps determine prognosis and likelihood of response to treatment. In addition, kidney biopsy can be performed to help assess genetic diseases. It is important to recognize that prognostication based on renal pathology alone may be affected by the sample size (particularly in lesions that are focal in nature) and may not be very accurate in biopsies with few glomeruli (ie, ?5). The findings in renal biopsy always need to be interpreted in the context of the clinical and laboratory features. Chronic changes (interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy), for example, are a sign of the magnitude and duration of prior injury.

OVERVIEW:

The routine evaluation of a percutaneous renal biopsy involves examination of the tissue under light, immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. Each component of the evaluation can provide important diagnostic information. The routine immunofluorescence examination of biopsy specimens should include (at a minimum) evaluation of IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, albumin, fibrin, and kappa and lambda immunoglobulin light chains. Special studies, including evaluation of serum Amyloid A deposits, IgG subclasses, and collagen chains, may be helpful in some cases where available.

Justification for the routine application of electron microscopy comes largely from earlier studies, which showed that this technique provided substantive diagnostic information beyond that obtained from light microscopy in nearly 50 percent of cases. However, most of these studies were performed at a time when immunofluorescence microscopy was not widely available.

To assess the utility of electron microscopy, a study of 288 native renal biopsies performed over a six-month period in 1996 examined the diagnostic findings provided by light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. When viewed in combination with the results from light and immunofluorescence microscopy, electron microscopy provided:

The routine evaluation of a percutaneous renal biopsy involves examination of the tissue under light, immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. Each component of the evaluation can provide important diagnostic information. The routine immunofluorescence examination of biopsy specimens should include (at a minimum) evaluation of IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, albumin, fibrin, and kappa and lambda immunoglobulin light chains. Special studies, including evaluation of serum Amyloid A deposits, IgG subclasses, and collagen chains, may be helpful in some cases where available.

Justification for the routine application of electron microscopy comes largely from earlier studies, which showed that this technique provided substantive diagnostic information beyond that obtained from light microscopy in nearly 50 percent of cases. However, most of these studies were performed at a time when immunofluorescence microscopy was not widely available.

To assess the utility of electron microscopy, a study of 288 native renal biopsies performed over a six-month period in 1996 examined the diagnostic findings provided by light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. When viewed in combination with the results from light and immunofluorescence microscopy, electron microscopy provided:

These findings are consistent with the results from earlier studies and support the continued use of routine electron microscopy.

INDICATIONS:

The indications for performing a renal biopsy varies among nephrologists, determined in part by the presenting signs and symptoms. The results of the renal biopsy impact patient care in up to 60 percent of cases. However, the utility of the biopsy may differ considerably based on the indication. Older age per se is not a contraindication to renal biopsy. Following are the main reasons for performing a diagnostic biopsy;

PREBIOPSY EVALUATION:

Prior to a percutaneous renal biopsy, a history, physical examination, and selected laboratory tests should be performed. The skin overlying the biopsy site should be free of signs of infection, and the blood pressure should be well-controlled. The patient should also be able to follow simple directions. Recommended laboratory tests include a complete biochemical profile, complete blood count, platelet count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time, if available. A bleeding diathesis, if discovered, should be appropriately evaluated and treated prior to undertaking a renal biopsy. A renal ultrasound should precede the biopsy to assess the size of and/or presence of any anatomic abnormalities that may preclude the performance of a percutaneous biopsy (for example, solitary kidney, polycystic kidney, malpositioned or horseshoe kidney, small echogenic kidneys, or hydronephrosis). The renal ultrasound is often performed at the time of the biopsy (unless it is done under CT guidance or as an open procedure by a surgeon). ince bleeding is the principal complication of renal biopsy, the evaluation should focus upon any evidence for a bleeding diathesis and the recent use of aspirin or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. To help ensure normal coagulation, patients should refrain from taking anti-platelet or antithrombotic agents (eg, aspirin, GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, persantine, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs) for at least one to two weeks prior to a scheduled elective biopsy and remain off of them for one to two weeks after the biopsy. Patients on heparin should have this stopped the day prior to the procedure.

RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS:

Percutaneous renal biopsy for the detection of primary renal disease is generally not pursued in the following settings:

While some contraindications may be considered relative in nature, absolute contraindications for the performance of a percutaneous native kidney renal biopsy include uncontrolled severe hypertension, uncontrollable bleeding diathesis, uncooperative patient, and a solitary native kidney. The absolute contraindication of biopsying a solitary kidney has been challenged due to the improved safety associated with newer imaging and biopsy techniques.

Patients on chronic anticoagulation: There are a number of issues that must be considered in patients on chronic anticoagulation in whom a renal biopsy is being considered. These include:

Thus, the management of patients chronically anticoagulated with warfarin must be individualized, often in consultation with hematology and cardiology, as appropriate.

An open or, if available, transjugular renal biopsy can be considered if the percutaneous approach is not feasible.

Solitary native kidney: A solitary native kidney has been considered an absolute contraindication to percutaneous biopsy, because of the concern that marked bleeding may lead to nephrectomy and loss of all of the patient's functioning renal mass. A surgically performed, open renal biopsy has been the procedure of choice in this setting.

TECHNIQUE:

All patients should provide informed consent for the biopsy. Possible allergy to local anesthetics and iodine containing solutions should be elicited. Just prior to the procedure, peripheral intravenous access is placed and the patient is usually placed prone with a pillow under the abdomen. Some anxious patients may require mild sedation, but when prescribing sedatives, caution should be taken and side effects considered.

All patients should provide informed consent for the biopsy. Possible allergy to local anesthetics and iodine containing solutions should be elicited. Just prior to the procedure, peripheral intravenous access is placed and the patient is usually placed prone with a pillow under the abdomen. Some anxious patients may require mild sedation, but when prescribing sedatives, caution should be taken and side effects considered.

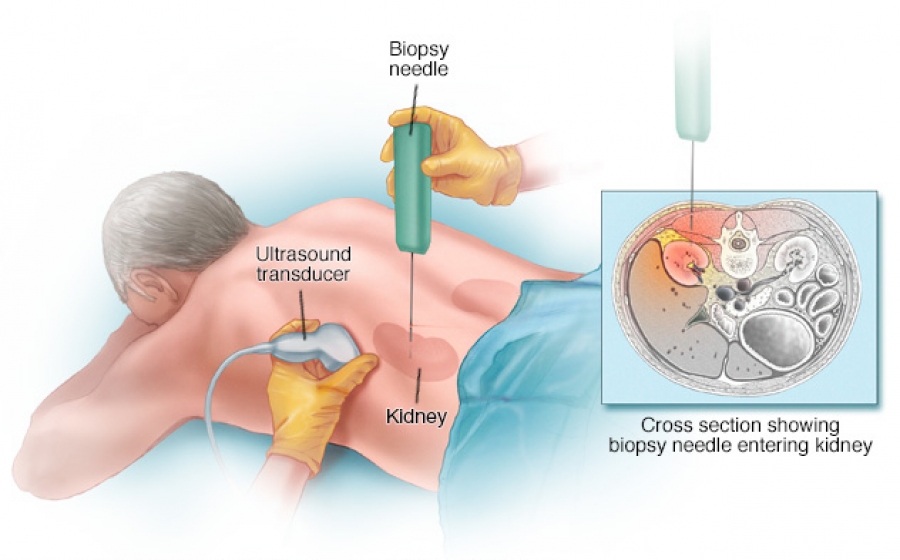

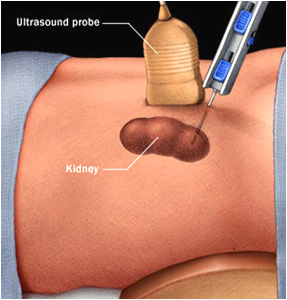

Percutaneous renal biopsy is usually performed under ultrasonic guidance with local anesthesia (usually 1 percent lidocaine hydrochloride). Ultrasonography can localize the desired lower pole site (at which the risk of puncturing a major vessel is minimized), determine renal size, and detect the unexpected presence of cysts that might necessitate using the contralateral kidney.

After the lower pole is localized, a skin mark is made to identify where the biopsy needle will be inserted. The site is subsequently prepped and anesthetized. Under ultrasound guidance, a spinal needle is then used to locate the capsule of the lower pole and to provide anesthesia for the biopsy needle tract.

After a small skin incision is made to facilitate passage, real time ultrasonography is most commonly used to guide the biopsy needle directly into the lower pole. This somewhat more cumbersome procedure has the advantage of direct visualization of the location of the needle as the core of tissue is obtained.

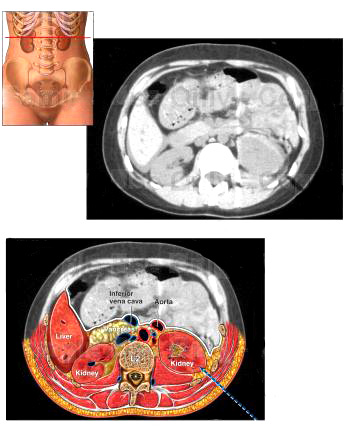

A CT scan is an alternative when the kidneys cannot be well visualized, as with marked obesity or small echogenic kidneys.

A variety of different biopsy needles are available, including manual needles (TruCut disposable, Franklin-Silverman, Vim-Silverman) and automated spring-loaded biopsy needles. The choice of biopsy needle is largely one of individual preference.

COMPLICATIONS:

Bleeding : Bleeding is the primary complication of renal biopsy. Most clinically significant bleeding is recognized within 12 to 24 hours of the biopsy.

As previously mentioned, the incidence of bleeding is minimized with normal partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, platelet count, and bleeding time. Additional clinical risk factors for bleeding include hypertension, renal insufficiency, and anemia. Prior reports suggested an increased risk of complication in certain disorders, such as autoimmune disease, end-stage renal disease, acute tubular necrosis, and amyloidosis.

The approximate incidence of the different bleeding complications is as follows, but is influenced by the expertise of the operator:

Other : The incidence of additional complications that may or may not be related to bleeding include:

POSTPROCEDURE OBSERVATION AND TIMING OF COMPLICATIONS:

The patient should be supine for four to six hours and then remain at bed rest overnight. To help detect bleeding and other complications, vital signs are closely monitored, and the urinalysis and complete blood count are obtained at various time points postbiopsy. To minimize the risk of bleeding, blood pressure should be well controlled (goal <140/90 mmHg).

An important question in this era of cost-containment is what is the optimal period of observation after renal biopsy. This is determined primarily by the time course of complications, particularly bleeding.

It was concluded that observation for 24 hours was optimal, with more than 90 percent of major complications being identified within this period. Thus, most patients should be observed overnight with monitoring of vital signs and a repeat hematocrit in the morning. However, in low risk patients (eg, serum creatinine concentration <2.5 mg/dL [221 micromol/L] blood pressure <140/90 mmHg, and no evidence of coagulopathy), a shorter observation period has been described.

Based on experience and published literature, I would recommend observing the patients for at least 12 hours and optimally up to 24 hours in the hospital at bedrest after biopsy.

NONPERCUTANEOUS RENAL BIOPSY TECHNIQUES:

Open renal biopsy: An open (surgical) renal biopsy (or a modified open biopsy done under local anesthesia) should be considered in three settings:

(1) when there is an uncorrectable bleeding diathesis, in which a transjugular biopsy is another alternative

(2) when there is a solitary kidney; and

(3) after failed attempts at percutaneous biopsy. A large core or wedge of renal cortex can usually be obtained, the incidence of severe bleeding is very low, and mortality is rare. Other relatively minor postoperative complications can occur, including fever, atelectasis, and ileus. In addition, an open biopsy under general anesthesia is associated with a longer hospital stay and a larger surgical scar.

Open renal biopsy has also been suggested in intensive care unit patients who are being mechanically ventilated. Even in this setting, however, it is possible to perform a percutaneous renal biopsy with portable ultrasonic guidance and the patient prone and being ventilated manually with an ambu bag.

Laparoscopic renal biopsy: Laparoscopic renal biopsy is advocated by some investigators as a viable alternative to open renal biopsy among patients unable or unwilling to undergo percutaneous renal biopsy.

Transjugular renal biopsy: Another technique is transjugular renal biopsy. This procedure is generally performed by an interventionalist in the angiography suite and requires a small amount of intravenous contrast.

The risk of perinephric bleeding is theoretically reduced since the renal capsule is not intentionally penetrated. In centers with experience, the complication rate of this technique is similar to the percutaneous approach. However, intrarenal bleeding due to arterial trauma may still occur, and some centers have reported high rates of bleeding due to capsular perforation. Contrast-induced nephropathy has also been reported. Another limitation of the procedure is that obtaining adequate tissue for establishing a diagnosis ranges from only 73 to 97 percent.

The major indication for this modality is an uncorrectable clotting disorder; other indications include the requirement for combined liver or heart and kidney biopsy, morbid obesity, or a single kidney.

Contraindications to a transjugular renal biopsy include bilateral internal jugular vein thrombosis, allergy to contrast media, and the lack of experienced clinicians. The greater cost in time, personnel, and radiologic guidance make this procedure impractical for routine renal biopsy, but may be an option in selected circumstances when the appropriate expertise is available.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS: