|

|

|

| |

Prof. (Dr.) Indranath Kundu

M.S. (Cal) Gold Medalist, D.N.B. (New Delhi)

Senior Consultant E.N.T. Surgeon

DEPARTMENT OF E.N.T.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

drinkundu@rediffmail.com |

+91 98300 35217

+033 2358 1260 |

|

|

|

| |

| Journals: |

| --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

| |

Osteoid osteoma of the ethmoid sinus: A rare diagnosis

April 30, 2012,

E. Bradley Strong, MD; James R. Tate, MD; Dariusz Borys, MD

ARTICLE

Abstract

Osteoid osteomas are benign osseous lesions. They have seldom been described in the otolaryngology literature, and they are extremely rare in the ethmoid sinuses. We report a new case of osteoid osteoma of the ethmoid sinus in a 15-year-old girl. The workup consisted of computed tomography. Treatment involved local excision via an external ethmoidectomy approach. The diagnosis was based on histopathologic examination.

Introduction Osteoid osteomas are benign osseous lesions that are extremely rare in the ethmoid sinuses. Osteoid osteomas can be easily identified radiologically by the presence of a central nidus surrounded by dense sclerotic bone on computed tomography (CT). In this article, we report a new case of osteoid osteoma that originated in the ethmoid...

Endoscopic view of an asymmetric roof of the ethmoid sinus

April 30, 2012,

Dewey A. Christmas, MD; Joseph P. Mirante, MD, FACS; Eiji Yanagisawa, MD, FACS

ARTICLE

It is important to study the anatomy of the roof of the ethmoid sinus both preoperatively and intraopereatively, especially to determine whether there are differences in the height and thickness of the left and right sides.

This patient who had sinus surgery 15 years previously presented with recurrent bilateral sinusitis involving the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses as shown by computed tomography (CT). Of note was the CT finding of marked differences in the ethmoid roof on the right and left sides. There was a significant difference in the height of the ethmoid roof...

Mycobacterial tuberculosis superimposed on a Warthin tumor

April 30, 2012,

Kang-Chao Wu, MD; Bo-Nien Chen, MD

ARTICLE

Abstract

The concomitant occurrence of tuberculosis infection within a Warthin tumor is extremely rare, as only 6 cases have been previously reported in the English-language literature. We report a new case in a 92-year-old man, who presented with a 20-year history of a painless swelling in the right infra-auricular area that had recently become painful and larger. The patient had no history of tuberculosis, weight loss, or chronic cough. The fluctuant mass was aspirated, but histopathology and routine culture were negative. Computed tomography identified a 5-cm, heterogeneous, enhancing mass with multiple, variably sized, low-density areas without surrounding edema in the area of the right parotid gland. Complete excision was performed to relieve the patient's symptoms. Histopathology diagnosed an acid-fast bacillus infection within a Warthin tumor. On polymerase chain reaction testing, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was negative for tuberculosis, but subsequent culture identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Initially, the patient refused antituberculosis therapy, but he relented when miliary pulmonary tuberculosis was diagnosed 11 weeks postoperatively.

Introduction Warthin tumor is the second most common tumor of the parotid gland.1 It has both epithelial and lymphoid components.1 Parotid tuberculosis (TB) is an uncommon clinical entity, accounting for only 2.8% of all parotid diseases.2 To the best of our knowledge, only 6 cases of TB infection within a Warthin tumor have been reported in the...

Bilateral congenital lacrimal fistulae: A case report

April 30, 2012,

Lei Zhuang, MD; Christin L. Sylvester, DO; Jeffrey P. Simons, MD

ARTICLE

Abstract

A congenital lacrimal fistula is a rare developmental anomaly, usually unilateral. While it is often asymptomatic, some patients present with epiphora or discharge. We report the case of a 4-year-old boy with bilateral lacrimal fistulae. No other systemic, nasal, or ocular anomalies were found. In the absence of significant symptoms, we decided on a course of observation. In this article, we discuss the embryologic basis of congenital lacrimal fistulae, as well as the typical presentation and possible treatment modalities. The presence of a lacrimal fistula is an indication to search for a variety of underlying systemic and ocular anomalies.

Introduction A congenital lacrimal fistula is a rare developmental anomaly that is caused by an interruption in the embryogenesis of the nasolacrimal system. While it is often asymptomatic, some patients present with epiphora or discharge that requires surgical intervention. Rasor described the first reported case of congenital lacrimal fistula in...

Killian-Jamieson diverticulum

April 30, 2012

Ashli K. O'Rourke, MD; Paul M. Weinberger, MD; Gregory N. Postma, MD

ARTICLE

Killian-Jamieson diverticulum is generally smaller than Zenker diverticulum and is associated with less dysphagia, regurgitation, and gastroesophageal reflux.

Giant tracheocele with multiple congenital anomalies

April 30, 2012

J. Madana, MS, DNB; Deeke Yolmo, MS; Sunil Kumar Saxena, MS; S. Gopalakrishnan, MS

ARTICLE

Abstract

Tracheocele-an outpouching of tracheal mucous membrane-is an uncommon entity. It can occur as a congenital or acquired form. The congenital entity remains mostly dormant until adulthood, and then it typically presents as a herniation with multiple air-filled sacs. The acquired form develops as the result of blunt trauma, recurrent pulmonary infection, intubation, instrumentation, or surgery, and it typically presents as a single paratracheal cavity. We present an extremely rare case of a tracheocele associated with multiple congenital anomalies involving the face, limbs, and heart.

Introduction Tracheocele is an uncommon abnormality that occurs as the result of the protrusion of mucosa through a defect in the tracheal wall. The protrusion leads to the formation of a large, single, air-filled cavity in the neck. Its pathophysiology differs from that of a tracheal diverticulum, in which multiple sacs develop.1,2

Primary acquired cholesteatoma

April 30, 2012

Joseph A. Ursick, MD; Jose N. Fayad, MD

ARTICLE

Cholesteatomas are believed to form as the result of poor eustachian tube function with resultant tympanic membrane retraction and a lack of normal epithelial migration.

A 40-year-old woman with a history of multiple ear infections as a child presented with right-sided hearing loss and aural pressure. Otoscopy revealed a pars flaccida retraction that contained crusted debris, as well as a white mass in the posterior mesotympanum (figure). The patient's audiogram showed a 25-dB right conductive hearing loss....

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the nasopharynx

April 30, 2012

Lester D.R. Thompson, MD

ARTICLE

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma accounts for more than 50% of all Waldeyer ring lymphomas, which in turn account for about 15% of all head and neck lymphomas and about 50% of all extranodal head and neck lymphomas.

Figure 1. A: Photograph shows a gross illustration of the “fish flesh” appearance of a cut lymphoid tumor. B: A vague nodularity is seen in this otherwise effaced nasopharyngeal tissue.

Laryngeal schwannoma excised under direct laryngoscopy: Case report

April 30, 2012

Iosif Vital, MD; Dan M. Fliss, MD; Jacob T. Cohen, MD

ARTICLE

Abstract

Laryngeal schwannomas (neurilemmomas) are extremely rare, and they present the otorhinolaryngologist with diagnostic and management challenges. These lesions usually present as a submucosal mass, and they are always a potential threat to the airway. We describe the case of a 75-year-old woman with a laryngeal schwannoma that arose from the left postcricoid area and covered the piriform sinus and arytenoid cartilage on that side. The tumor was completely excised under direct laryngoscopy with the use of a CO2 laser, and preservation of the mucosal lining of the larynx was achieved.

Introduction Schwannomas (neurilemmomas) are benign encapsulated tumors that originate in the Schwann cells that sheathe the fibers of the peripheral, cranial, and autonomic nerves outside the central nervous system.1, 2 Malignant transformation is rare. The head and neck region is frequently involved (25 to 45% of cases), but schwannomas of the...

Primary intraosseous cavernous hemangioma of the zygoma: A case report and literature review

April 30, 2012

Anna M. Marcinow, MD; Matthew J. Provenzano, MD; Richard K. Gurgel, MD; Kristi E. Chang, MD

ARTICLE

Abstract

Intraosseous hemangiomas are rare. We report the case of a 47-year-old man who presented with a gradually enlarging left zygomatic mass that had caused pain, deformity, and superficial soft-tissue swelling. Computed tomography revealed a well-circumscribed 2.0 x 2.5-cm mass with a ground-glass matrix in the left zygoma. Following surgical excision, the patient's symptoms resolved. Findings on pathologic examination of the excised tissue were consistent with an intraosseous cavernous hemangioma. We describe the features of this rare case, we discuss the pertinent radiologic features and pathophysiology of intraosseous hemangiomas, and we review the available literature.

Introduction Intraosseous hemangiomas account for less than 1% of all tumors.1 Their most common sites are the calvaria and the vertebral column.1 Their presence in the midface, including the zygoma, has been described only in a few isolated case reports 2. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Articles: |

| |

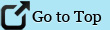

| Columellar deformity, above (eg, Ivy modification of the Blair technique, Dingman technique) may also be used. |

|

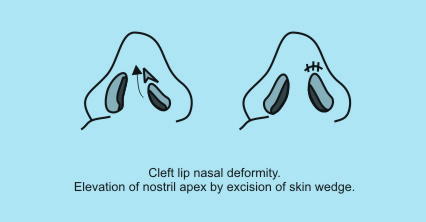

| Internal approaches – in the Thomas Rees technique the alar cartilage is severed from its lateral attachment and advanced medially to be sutured to the contralateral ala. |

|

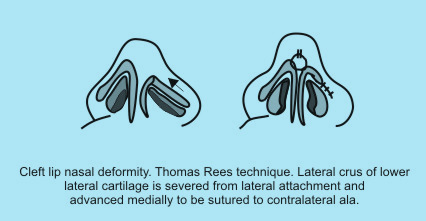

The classic Tajima reverse-U technique has undergone many modifications. A reverse-U intranasal incision is made on the cleft side, the subcutaneous pocket is developed, and the deformed ala is sutured to the ipsilateral upper lateral cartilage, the contralateral upper lateral cartilage, and the contralateral ala. |

|

Correction of septal deflection may be sufficient to reestablish normal dorsal symmetry. Advocates of early septal surgery cite the benefit of more normal nose growth, including the dorsal aspect. At times, osteotomies may be required to correct dorsal deflection. Onlay cartilage grafts have also been used to add bulk to the underdeveloped cleft side.

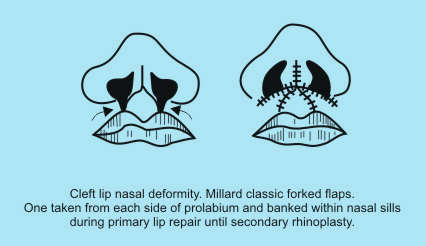

The hallmark of bilateral cleft lip nose is a short columella. Millard popularized what is perhaps the best known columellar lengthening technique. He advocated the use of forked flaps, one from each side of the prolabium, which are banked within the nasal sills during primary lip repair until secondary rhinoplasty is performed. These flaps are then retrieved and rotated into the columella of the child when aged 2-4 years to achieve columellar lengthening. |

|

However, McComb reviewed his cases of primary columellar repair using forked flaps and discovered that by adolescence, 3 unfavorable features developed:

1.The columella overlengthens

2.The nasal tip broadens

3.Downward drift of the lip-columellar junction occurs in conjunction with an unsightly transverse scar.4

Therefore, McComb discourages borrowing tissue from the prolabium and favors using only nasal tissue to reconstruct the columella. McComb argues that surgical repair should focus on reestablishing normal alar shape, which in turn naturally elongates the columella. McComb achieves this result by suturing the medial crura of the alar cartilages together, which lengthens the columella and corrects the broadened nasal tip.

Mulliken states that the already flattened nasal ala continues to separate over time as a result of muscle tension.5 Therefore, Mulliken favors primary alar correction, as does McComb, to achieve columellar length and proper nasal tip shape.

Outcome and Prognosis-

Cleft lip nasal deformity is a complex anomaly, and proper correction requires considerable surgical talent and experience. Outcome assessment after cleft lip repair is based on lip contour and symmetry, facial growth, and psychological well-being. Surgeons must continue to tailor approaches to individuals and evolve techniques to best serve each patient. Children who benefit from good surgical repair have a chance to mature with fewer psychological sequelae from this deformity.6

Major revisional surgery is not usually needed after cleft lip repair. Minor revisions of the vermilion or scar revision may be needed. The most challenging aspect of cleft lip surgery is correction of nasal deformity. Secondary surgery to improve nasal contour and symmetry is commonly required.

Future and Controversies-

Recombinant DNA technology has revolutionized the ability to detect molecular defects at the protein and gene level; however, a clear understanding of the molecular basis of clefts has yet to be discovered. Some studies have suggested that several genes may be involved, including transforming growth factor–alpha, retinoic acid receptor–alpha, BCL3, and MSX-1.

The experimental finding that fetal wounds made early in gestation heal without scar formation sparked an interest in intrauterine repair of the cleft lip. However at the present time, the risk of preterm labor and fetal loss is too high to justify the use of fetal surgery for the correction of cleft lip.

Neonatal lip repair is controversial. Proponents of neonatal repair cite the potential psychological benefits of bringing home a child with normal appearance; however, this assertion remains unproven. Such early repair may be associated with an increase in perioperative risk.

Controversy exists regarding the use of presurgical orthopedics or lip adhesion. Lip adhesion may be indicated for wide unilateral complete clefts. Those that oppose this technique argue that the scar introduced in the adhesion may interfere with subsequent cheiloplasty. A well-planned and executed lip adhesion may facilitate cleft repair while introducing a fine scar. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Otosclerosis:

Jan 25, 2012 |

| |

Introduction:

Otosclerosis is a progressive otic capsule disease characterized by abnormal new bone formation that affects only human beings through changes in the middle and inner ear. It can occur independently or together at the stapes footplate, and/or the cochlear capsule.

Otosclerosis is an osseous dyscrasia limited to the temporal bone slowly resulting in progressive conductive hearing loss.

Histologic otosclerosis is defined as an incidental finding in temporal bone autopsies; however, when otosclerosis fixes the stapes footplate it causes conductive hearing loss and is defined as clinical otosclerosis

Etiology:

Otosclerosis is a process of bone remodeling in the otic capsule that has a unique remodeling process different than other parts of the body.1 Even though little or no bone remodeling is seen in the otic capsule under normal conditions, remodeling may start when certain molecular factors trigger the otic capsule in patients who have genetic and/or environmental tendencies.2

Evidence supports the thesis that otosclerosis is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with incomplete penetrance.3-9

The exact cause of otosclerosis is unknown. Measles virus RNA is found in otosclerotic foci in footplates removed during surgery [17-19].10-12 Measles virus infection may activate the gene responsible for otosclerosis. Otosclerosis, however, is not responsible for all cases of stapes ankylosis. A heterogeneous group of disorders, including other bone degenerative disorders, appears to cause stapes fixation and conductive hearing loss.

Histopathology:

The lesion is a pleomorphic replacement of normal bone with spongiotic or sclerotic bone. The histiologic disease progresses in stages. Bony resorption and replacement with new spongy bone characterize early lesions. Osteolytic osteocytes appear at the leading edge of the lesion, and sheets of connective tissue can be observed replacing the bone. Formation of dense sclerotic bone in areas of previous resorption signifies the late phase of otosclerosis. The result is disorganized bone, increased population of osteocytes, and enlarged marrow spaces containing vessels and other connective tissue. Spaces are later replaced by dense sclerotic bone with narrow vasculature and few recognizable haversian systems. Pleomorphism is largely due to normal coexistence of both stages of otosclerosis in any single temporal bone.

The sensorineural hearing loss starts to appear when the otosclerotic focus reaches the cochlear endosteum.13 Later on, atrophy of the spiral ligament and stria vascularis, as well as the formation of hyalinization in the spiral ligament; have been seen to be responsible for the hearing impairment by hindering recycling ions and by reducing the endocochlear potential with subsequent cochlear hair cell dysfunction.14 A study showed that cochlear otosclerosis adjacent to the round window caused more damage to spiral ganglion cells and outer hair cells than cochlear otosclerosis adjacent to the oval window.15 On the other hand, cochlear otosclerosis adjacent to the oval window caused more damage in the spiral ligament by ending up with a hyalinized and atrophied spiral ligament.

Clinical Manifestations:

As with any disease, a careful history and thorough physical examination are prerequisites. Often this process reveals a family history of otosclerosis. Symptom onset usually occurs by the early third decade of life, but onset is not unusual later in life.

The clinical course of the disease depends on the progression of the cochlear otosclerosis and its otic capsule involvement. In addition to sensorineural or mixed type hearing loss, which is bilateral in 70% of cases, tinnitus (common) and vertigo (less common) can also occur in patients with cochlear otosclerosis.

On physical examination, patients with conductive hearing loss often exhibit low-volume speech because they perceive their own voices louder because of the enhanced bone conduction of sound. Otoscopic examination findings are usually normal, although 10% of patients demonstrate a Schwartze sign, characterized by a reddish-blue hue over the promontory and oval window niche areas, secondary to rich vascular supply associated with immature bone. Tuning-fork examination reveals signs of conductive hearing loss.

Early in the disease course, pure-tone audiometry usually demonstrates low-frequency conductive hearing loss. High-frequency losses begin to manifest with gradual air-bone gap widening.

Otosclerosis can be associated with an increased incidence of vestibular symptoms.16-18 It has been assumed that the dizziness could be due to the changes in the biochemical composition of the perilymph.19,20 Vestibular symptoms associated with otosclerosis can be recurrent, positional, or spontaneous. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is seen in patients with extensive otosclerosis.21

Investigations:

A full audiometric evaluation, including impedance testing, is necessary. A reduction in bone conduction sensitivity with a peak at 2.000 Hz is an audiological marker for otosclerosis.

On computerized tomography (CT), a distinctive pericochlear hypodense double ring appearance due to demineralization of the bone around the cochlea is seen in patients with cochlear otosclerosis.22 Since active otosclerosis will appear as a hypodense ring within the otic capsule, CT of the temporal bone will only detect active otosclerosis.

Even though the temporal bone and otosclerosis is best characterized on high resolution CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may suggest central causes in patients with sensorineural hearing loss. MRI demonstrates a ring of intermediate signal in the pericochlear and perilabyrinthine regions on T1 weighted images, and demonstrates mild to moderate enhancement after gadolinium administration. MRI shows perilabyrinthine and pericochlear soft tissue with contrast enhancement. T2 weighted images also show increased signals.

Treatment-

1. Medical:

Sodium Fluoride that is very safe in therapeutic doses may be effective if there is active otosclerosis focus. The idea came from comparable studies indicating the high incidence of clinical otosclerosis in low-fluoride areas.23 The adverse reactions reported during fluoride treatment included synovitis, plantar fasciitis, gastrointestinal side effects such as recurrent vomiting, peptic ulcer, anemia, and increased skeletal fragility.24,25 The dosage can be adjusted starting with 60 mg and continuing with the maintenance dosage of 20–25 mg if clinical proof of effectiveness of the treatment is seen.24-28 Researchers found out that fluoride treatment is more effective for the higher frequencies in cases with cochlear otosclerosis and an initial sensorineural hearing loss of less than 50dB.29

Biphosphonates also have a potential use in the treatment of cochlear otosclerosis by inhibiting the activation of osteoclasts.30 Research shows that with etidronate there is a 70% improvement in their hearing, 54% in dizziness, and 52% in tinnitus in patients with otosclerosis.31 Adverse effects with biphosphonates are rare.

As with conductive hearing losses of other etiologies, hearing aids are usually helpful.

2. Surgical:

Surgical management of otosclerosis includes:

•Total stapedectomy

•Partial stapedectomy

•Stapedotomy

•Cochlear implant

Surgery is typically performed on an outpatient basis. Unless experiencing significant vertigo or emesis, patients are usually safe to leave the hospital within a few postoperative hours. Bed rest is necessary only in the immediate postoperative period.

It has been reported that there is a significant risk of cochlear ossification and facial nerve stimulation after cochlear implantation in patients with cochlear otosclerosis and profound sensorineural hearing loss.32

Commonly quoted statistics indicate that 90% of appropriately chosen surgical candidates enjoy a significant hearing improvement. Eight percent experience no significant hearing improvement. Up to 2% (including 0.2% who may experience complete sensorineural hearing loss in the operative ear) experience additional hearing loss. Revision stapes surgery yields less-successful results than primary surgery. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma:

Dec 26, 2011 |

| |

Introduction:

Carcinoma of the thyroid gland is an uncommon cancer but is the most common malignancy of the endocrine system.1 Four general types of thyroid cancer are papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic. Except for anaplastic and metastatic medullary carcinoma, most thyroid cancers are not highly malignant and are seldom fatal.

Papillary carcinoma is a relatively common well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Though papillary carcinomas are well differentiated, they may be minimally or overtly invasive. They are more likely to invade the lymphatics and rarely invade the blood vessels. Papillary carcinoma appears as an irregular solid or cystic mass in a normal thyroid parenchyma.

About 11% of patients with papillary carcinoma present with metastases outside the neck and mediastinum. Some years ago, lymph node metastases in the cervical area were thought to be aberrant (supernumerary) thyroids because they contained well-differentiated papillary thyroid cancer.2-7

Risk Factors:

Patients with a history of radiation administered in infancy and childhood for benign conditions of the head and neck have an increased risk of cancer. In this group of patients, malignancies of the thyroid gland first appear beginning as early as 5 years following radiation and may appear 20 or more years later.8

A relationship between iodine deficiency and the incidence of thyroid carcinomas is firmly established. Other risk factors9-11 for the development of thyroid cancer include the following:

•A history of goiter

•Family history of thyroid disease

•Female gender

•Oral contraceptive use

•Late menarche

•Late age at first birth

•Asian race

Pathophysiology:

Papillary thyroid carcinoma seems closely related to the activation of Trk and Ret proto-oncogenes, both acting by amplifying and rearranging mechanisms. In addition, evidence suggests that some molecules that physiologically regulate the growth of the thyrocytes, such as interleukin-1 and interleukin-8, or other cytokines could play a role in the pathogenesis of this cancer.

Incidence:

Thyroid cancers are quite rare, accounting for only 1.5% of all cancers in adults and 3% of all cancers in children, but the rate of new cases is increasing in the last decades. Papillary carcinoma accounts for 70 to 80% of all thyroid cancers. The female:male ratio is 3:1. It may be familial in up to 5% of patients. Thyroid carcinoma is common in persons of all ages, with a mean age of 49 years and an age range of 15-84 years. Most patients present between ages 30 and 60.

The overall incidence of incidental papillary carcinoma (IPC) in benign operatively resected thyroid disease is 12%, with Hashimoto thyroiditis being associated with the highest rate of IPC.12 Contralateral IPC was encountered in 40% of patients (6 of 15 patients) with follicular adenoma. Total thyroidectomy may be considered appropriate in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis and follicular adenoma requiring operation.

Morbidity and Mortality:

In contrast to other cancers, thyroid cancer is almost always curable. Most thyroid cancers grow slowly and are associated with a very favorable prognosis. The mean survival rate after 10 years is higher than 90% and is 100% in very young patients with minimal non-metastatic disease.

•Distant spread (i.e. to lungs or bones) is very uncommon.

•The mean mortality rate is 1.5% for females and 1.4% for males.

The 5-year relative survival rates by stage of diagnosis are provided below13:

•All stages: 96.7%

•Local: 99.7%

•Regional: 96.9%

•Distant: 56%

Signs and Symptoms:

Many cases of papillary thyroid cancer are subclinical. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic thyroid mass or a nodule that can be felt in the neck. If a thyroid lump has developed recently, obtain a history regarding every prior exposure to ionizing radiation and the lifetime duration of the radiation exposure. Also consider a family history of thyroid cancer.

Some patients have persistent cough, difficulty breathing, or difficulty swallowing. Other symptoms like pain, stridor, vocal cord paralysis, hemoptysis, rapid enlargement are rare. At the time of diagnosis, 10-15% of patients have distant metastases to the bones and lungs.

On examination there is a palpable, firm, painless and non-tender nodule in the thyroid area. With thyroid palpation, a usually solitary nodule that has a hard consistency, an average size of less than 5 cm, and ill-defined borders can be felt. This nodule is fixed in respect to surrounding tissues and moves with the trachea at swallowing. Signs of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism are usually not observed.

Laboratory Investigations:

Higher-than-normal levels of thyroxine, triiodothyronine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone may indicate thyroid cancer.

Evaluate serum levels of thyroglobulin, calcium, and calcitonin.

Serum level of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may be helpful.

TSH suppression test - When exogenous thyroid hormone feeds back to the pituitary to decrease the production of TSH, thyroid nodules that continue to enlarge are likely to be malignant. Postoperatively, the test is useful for monitoring papillary thyroid cancer cases.

Imaging Studies:

Chest radiography, CT scanning, and MRI are not usually used in the initial workup of a thyroid nodule. These tests are second-level diagnostic tools and are useful in preoperative patient assessment.

Ultrasonography is the most sensitive procedure for identifying thyroid lesions and for determining the size of a nodule (2-3 mm). It is also useful for localizing lesions when a nodule is difficult to palpate or is deeply seated, and can help determine if a lesion is solid or cystic and can help detect the presence of calcifications. The accuracy rate of ultrasonography in categorizing nodules as solid, cystic, or mixed is near 90%.

Doppler studies may provide important information about the vascular pattern and the velocimetric parameters.

Thyroid scanning performed with radioactive iodine (iodine I 131 or iodine I 123) was the initial diagnostic procedure of choice for a thyroid evaluation. However, the procedure is not as sensitive or specific as FNAB for distinguishing benign nodules from malignant nodules. In more than 90% of cases, clearly benign nodules appear as hot nodules, whereas malignant nodules

Diagnostic Procedure:

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is considered the best first-line diagnostic procedure for a thyroid nodule. FNAB is a safe and minimally invasive procedure. The sensitivity of the procedure is near 80%, the specificity is near 100%, and errors can be diminished using ultrasonographic guidance. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|